This article was first published as "The battle for the SX-70." It appeared in the May 1989 issue of IEEE Spectrum. A PDF version is available on IEEE Xplore. The diagrams and photographs appeared in the original print version.

Yet this complicated system had to fit in a package the size of Land’s jacket pocket, he decreed—a constraint that meant employing ICs. But as Polaroid could not fabricate ICs, the success of its SX-70 project lay in the hands of outsiders.

The flash control contract was given to General Electric Co. Then in 1971, when GE dropped out of the IC business, it was issued to Sprague Electric Corp., as well as to Fairchild Semiconductor Corp. of Palo Alto, Calif., and Texas Instruments Inc. of Dallas, Texas. Only Fairchild and Sprague ended up producing flash controllers.

Independent contracts to develop the motor and exposure control modules went to Fairchild and TI. The motor control module contained a linear control IC, an NPN motor drive transistor, and a discrete PNP dynamic braking transistor, and gave the designers little trouble. The exposure control module was a different story.

The grand challenge

Included in the exposure control were three ICs (early Fairchild versions had four). The exposure timer used the current output of a silicon photodiode to regulate how long the shutter blades remained open. The delay-timing circuit generated four intervals: a delay of 40 milliseconds before the shutter opened; the time the shutter remained open before the flash was fired; the duration of the flash; and the maximum exposure time given certain ambient lighting. The power control IC drove the solenoids and motor control unit. And this all had to fit on a board that fit into a 27-by-95-by-2-millimeter space, minus a central hole for the camera lens.

Electrical noise was a major stumbling block. The photocell, for instance, operating with as little as 15 picoamperes, had to maintain its state in an environment in which the motor, the solenoids, and the firing of the flash lamps drew amperes of current. Designers were to take steps like inserting a delay between the release of the solenoids and the start of the photocell-timed exposure; redesigning circuitry on the power supply line to reject noise from the motor; increasing the voltage difference between logic highs and lows, so noise spikes would no longer masquerade as bits; and including a low-pass filter.

As it was 1969, there were no semicustom ICs, gate array technology was in its infancy, and only primitive packaging was available—standard dual in-line packages (DIPs) were at least 0.125 inch thick—while logic and power transistors could not yet share the same piece of silicon. And Polaroid wanted to buy this exposure controller for US $5.75.

What friends are for

Polaroid chairman Land and TI chairman Patrick Haggerty were old friends. On a weekend trip decades before the SX-70 project, they had discussed how electronics might one day make a truly one-step camera possible. The idea was to work on this dream together as soon as the technology arrived. So it came as no surprise when TI was charged with developing the camera’s exposure control board. Land was counting on TI for a fail-safe design, based on analog circuitry and proven technology and therefore reliable, reasonably priced, and capable of being produced on schedule.

Polaroid also asked Fairchild, which it viewed as the country’s leader in IC technology, to tackle a design that would push the state of the art. Fairchild’s version was to be digital and highly integrated, even to combining power transistors with logic on one chip. To Polaroid the approach looked risky, but its engineers were excited by its possibilities. Still, some within Polaroid thought the Land-Haggerty relationship made nonsense of using anyone but TI.

In the dark

The R&D contracts were awarded in 1969, and the competitors went to work, both with the same handicap: incomplete information. Fearing that Kodak Corp. might enter the instant camera business, Polaroid wanted no leaks—so much so that it mentioned neither the new film nor the fact that at one point the camera was redesigned as an SLR—and kept the design teams from seeing a prototype of the camera. (Although TI’s then executive vice president, the now-retired Fred Bucy, saw a demonstration of the early, non-SLR SX-70 in 1969, he said nothing about it to the company’s engineers.) Said Peter Carcia, an engineer on the SX-70 project and still with Polaroid: “They had very little to work with”—only stacks of specifications.

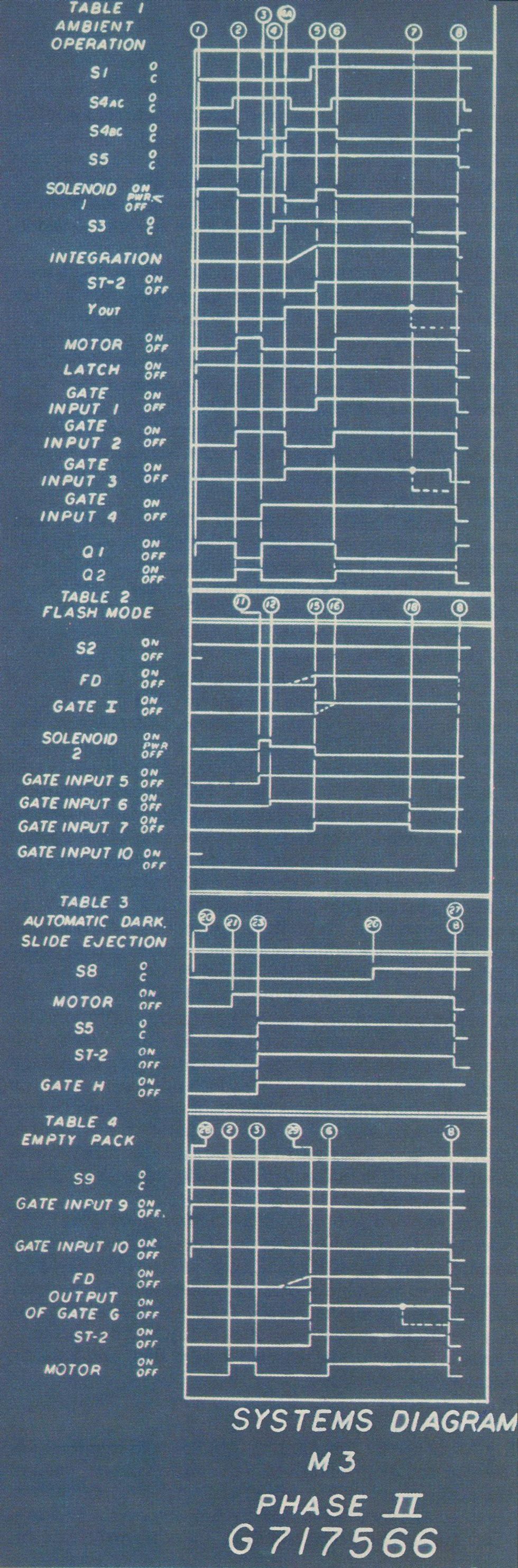

When it contracted with Fairchild and TI to develop the electronics for the SX-70 camera, Polaroid Corp. provided this timing diagram along with 30 pages of other design specifications, reliability requirements, and test information. It indicates sequences of events for the four different modes of operation a fully automatic camera required. Table 1 indicates functions for taking photographs in ambient light, Table 2 covers flash operation, Table 3 calls out the sequence of events that is triggered when a new film pack is installed and its protective cover must be ejected, and Table 4 describes the operations that occur when a pack of film is used up.

Polaroid engineers recall that loads on the electronics were described simply as inductive, and that details of the battery supply were vague because a new battery was being concurrently designed.

“We didn’t tell them whether a load on the electronics was from a solenoid or a relay, just that it was an inductive load,” recalls Seymour Ellin, now a senior technical manager at Polaroid.

“Since we were making our own battery [designed concurrently], we couldn’t tell them what the battery supply would be,” said Carcia. “I would tell them ‘I want you to design a circuit, but I won’t tell you what the power source will be,’ and they would look at me strangely.”

Polaroid wanted no leaks—so much so that it mentioned neither the new film nor the fact that at one point the camera was redesigned as an SLR.

Even worse was the “Y” delay—which Polaroid engineers told IEEE Spectrum came from the “why” response given Fairchild and TI engineers whenever they questioned one specification: the short delay before starting the exposure, after the user pressed the button. This pause was to allow the mirror (which in an SLR camera reflects the image seen through the lens to the viewfinder) to stop vibrating after it snapped out of the way of the film to be exposed. But that was more than Polaroid wanted to divulge. The sources of the noise problem were left obscure, and its extent understated, said Clark Williams, then a TI design engineer. “That motor pulled 3 amps of current and put out a rich spectrum of noise that played havoc with our circuits,” he said. (He is now a design manager at Dallas Semiconductor Corp. in Dallas, Texas.)

The TI team, unable to base a breadboard on Polaroid’s diagrams alone, sent two engineers and several technicians to Cambridge to work in a little private room there. Whenever they needed to test their breadboard, they would hand it over to Polaroid engineers, who would carry it to another room and eventually report back that, say, a certain signal needed adjustment or a certain section did not function. The TI engineers would make a few adjustments, then the breadboard was carried off for another test. This to-and-fro-ing went on for six months, whereas, said Michael Callahan, a senior TI design engineer who is presently executive vice president of engineering at Crystal Semiconductors Corp. in Austin, Texas: “We could have done the work in two weeks if they had let us sign nondisclosure agreements.”

Designing in Dallas

A preliminary round had disappointed both IC teams. In 1969, before Polaroid had firmed up many SX-70 details, it started both TI and Fairchild developing simple exposure control chips. This early effort, said Polaroid engineers, was also used to develop and test their working relationship with Fairchild. But the SX-70 project changed so much, particularly with its redefinition as an SLR camera, that Polaroid decided to start over. Callahan and Ken Buss, now a senior member of the technical staff at TI, recall a meeting in Dallas at which the TI engineers proudly demonstrated the working circuits—only to have Polaroid ignore them and announce its new requirements.

“That made our chips instantly obsolete,” Buss said. At Fairchild, too, enthusiasm flagged. Coincidentally, both companies soon after underwent a corporate restructuring, but whereas the changes at Fairchild benefited its SX-70 team, those at TI nearly cost it everything.

The TI designers, instead of working directly with Polaroid, were told to report to the Assembled Functions Group. Lacking either chip development or manufacturing facilities of its own, the Group contracted with the IC designers’ department to develop three chips—a photocell amplifier to determine the correct exposure, a chip to control the motor and handle dynamic braking, and a chip to handle timing, count the film used, and serve other functions—and with another department to manufacture the chips. The arrangement further filtered the already limited information from Polaroid.

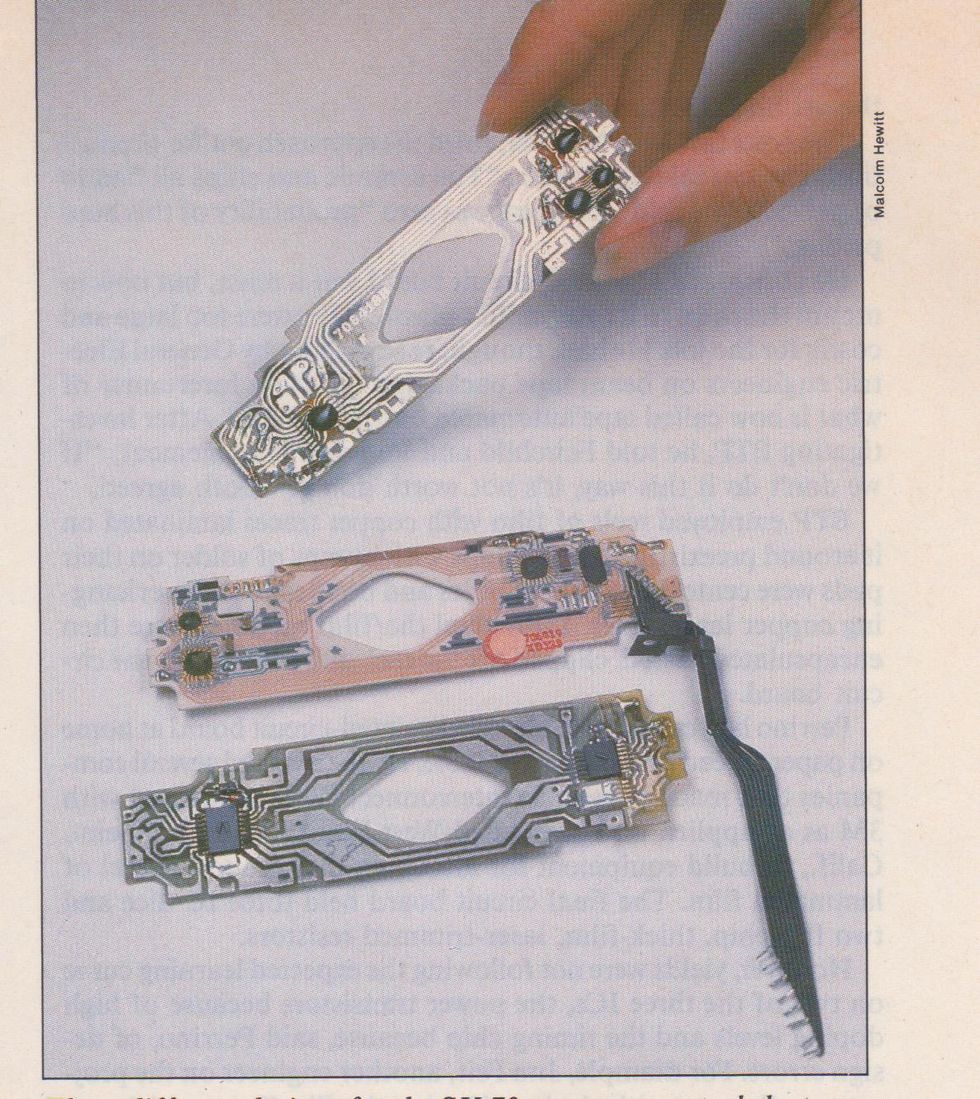

Three different designs for the SX-70 exposure control electronics were produced. Fairchild Semiconductor Corp.’s version (top) went into cameras in 1972 and 1973—notice the polyimide film used to attach the ICs to the board. Texas Instruments Inc. produced its ceramic board (center) during 1972, then redesigned, and won the manufacturing contract away from Fairchild with a circuit board that used miniDIP IC packaging (bottom).

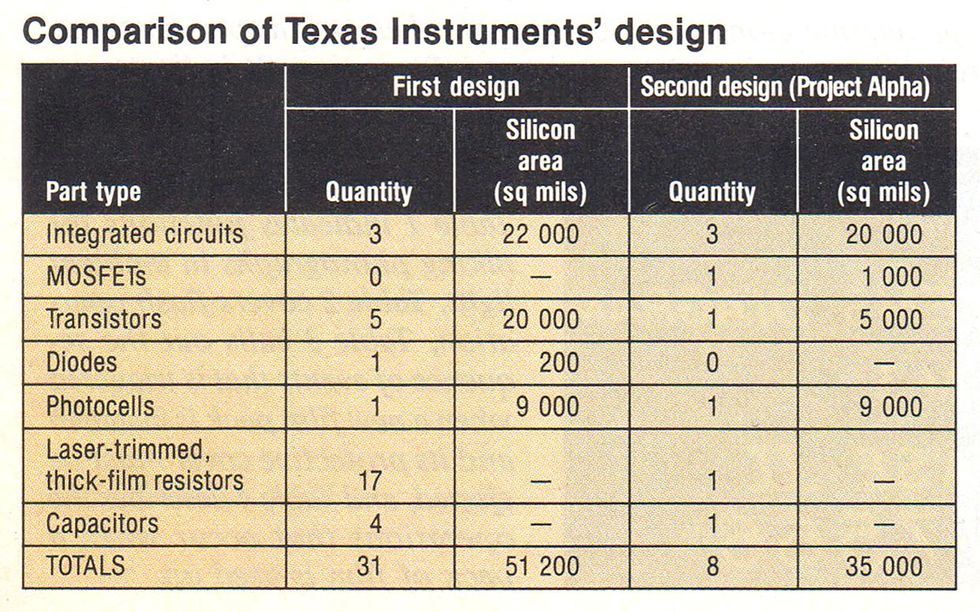

That left the Group itself with the job of designing the circuitry that would tie the ICs together. Its engineers used 13 discrete transistors, 17 laser-trimmed thick-film resistors, and a photodiode, intending to mount them on a printed-circuit board. Management instead mandated a ceramic substrate essentially because, said one TI design engineer, the Group reported to the same manager as TI’s Hybrid Thick-Film Group, which had excess capacity.

“We knew we couldn’t meet the cost goals with a ceramic substrate,” he said. The ceramic, the precious metal conductors, and the labor all cost too much for the substrate to serve as anything more than a prototype “to let us get all the circuitry in a small area.” And when the design grew from 3/4 square inch to 4 or 5 square inches (from 5 to 25 or 32 square centimeters), the engineer recalled, he and the other designers predicted major manufacturing problems and urged doing a more digital redesign with a printed-circuit board. But management “wouldn’t listen,” he said.

TI’s ceramic-based design did, however, perform to Polaroid’s specifications, and it went into production in late 1972. But it was indeed a nightmare. First, at $100 a unit, it was nowhere near the $5.75 cost goal. And manufacturing problems were tremendous, especially with the gigantic and therefore fragile ceramic substrate. For instance, said TI design engineer Norm Culp: “We had to take a chip, alloy it to a Kapton film carrier [a high temperature plastic foil], then wire bond the chip to the Kapton carrier, then encapsulate the chip. The Kapton film carriers were then tested individually, then reflowed onto the ceramic substrate.”

Yield was about 1 percent, and that one in 100 sometimes cracked on its way to Polaroid.

Moreover, said Culp, reflow-soldering chip carriers to the substrate caused microcracks in the ceramic, and for a while TI inspected every part for the flaws. Then one engineer realized that heating the entire substrate instead of just the part to be reflow-soldered would reduce the microcracks, which, however, showed up in other parts of the process. Yield was about 1 percent, and that one in 100 sometimes cracked on its way to Polaroid.

Polaroid did order several hundred of these ceramic modules to get the SX-70 to market. But it wasn’t at all happy with them. Said Ellin, “TI, essentially, failed to meet the cost objective.”

Competing in California

Meanwhile, engineers at Fairchild were also running into difficulties, but technical ones only. Early in the design process, Fairchild’s corporate restructuring moved the R&D engineers out of their isolated laboratory into operating divisions, making for better communication with manufacturing, which “resolved a lot of problems,” said Howard Murphy, a senior member of the Fairchild research staff and the project director for the SX-70 electronics.

"We designed a die that had around 20 flip-flops on it, probably a new high in IC complexity at that time.”—Howard Murphy, Fairchild

One design problem was high temperature. Murphy recalled that the heat of the heavy currents drawn by the motors and the solenoids affected the control logic circuitry, which then had to be redesigned to work at higher temperatures—the specifications indicated 40 °C. Another hurdle was the photo circuit. It had to time out after 20 seconds, so that pictures could be taken in dim light of about 0.06 candela per square foot (0.65 candela per square meter), although the circuit design team wasn’t fully aware of the reason for this at the time. The circuit also had to be very small and consume just a few milliamperes. “So we designed a die that had around 20 flip-flops on it, probably a new high in IC complexity at that time,” Murphy remembered.

Frank Perrino, a Fairchild product manager, first became involved in the SX-70 project in May 1971, when he oversaw its move into manufacturing. He recalled that the designers were then working on four chips—a driver for the motor and solenoids, a timing chip, and the photodiode and photodiode amplification chips that later became one bipolar CMOS IC. The dice were to be mounted directly on an irregularly shaped 1-by-4-inch ceramic substrate previously metalized on both sides with state-of-the-art lines and spaces.

The costs involved, however, ruled the approach out for production, Perrino told Spectrum. “The ceramic and chips all had to be perfect,” he said, and there was zero “probability of this happening.”

He concluded a printed-circuit board was a must, but how to mount the chips to it? Fairchild’s plastic DIPs were too large and costly for the job. He had, though, read a paper by General Electric engineers on beam tape packaging (BTP), a forerunner of what is now called tape automated bonding (TAB). After investigating BTP, he told Fairchild and Polaroid management, “If we don’t do it this way, it’s not worth doing.” Both agreed.

BTP employed reels of film with copper traces laminated on it around preexisting holes. Chips with bumps of solder on their pads were centered under the holes and bonded to the overhanging copper lead frames. Individual die/film modules were then encapsulated, tested, clipped off the reel, and soldered to the circuit board.

Perrino laid out the double-sided printed-circuit board at home on paper spread across his pool table. He then visited several companies that made polyimide interconnect film, contracted with 3M as a supplier, and persuaded West-Bond Inc. of Anaheim, Calif., to build equipment for attaching the dice to the reel of laminated film. The final circuit board held three IC dice and two flip-chip, thick-film, laser-trimmed resistors.

However, yields were not following the expected learning curve on two of the three ICs, the power transistors because of high doping levels and the timing chip because, said Perrino, of design errors. For example, Jim Feit, another engineer on the project, recalls a parasitic device affecting the flip-flops, which was fixed with the addition of a delay.

Still, though the parts were not cheap, costing Fairchild approximately $20 or $30 each, they were manufacturable.

D-day

The SX-70 was introduced in April 1972, in conjunction with the company’s annual stockholders’ meeting. A year earlier, Land had teased the stockholders by pulling a prototype SX-70 out of his pocket and waving it in the air. That was a working model, containing one of TI’s first successful ceramic circuit boards. But for this meeting, Polaroid needed 20 cameras, and John Burgarella, now retired from the company, had to make several trips to Texas to hand-carry enough working boards back to Cambridge. About a month earlier, Land had brought Fairchild engineers Perrino, Murphy, and Will Steffe to his Cambridge office and demonstrated the camera to them. “It was obviously a technological breakthrough,” recalled Perrino, which motivated them “to go back and make the thing work.”

Edwin Land showed the first working SX-70 camera at a stockholders’ meeting in 1971. It was only a prototype, and contained one of the first working ceramic circuit boards produced by Texas Instruments. A TI engineer had installed it the night before the meeting, working with a camera that was shrouded to prevent him from learning anything more about it than he already knew.

The introduction went off without a hitch. About a dozen scenes, from a poker game to a child’s birthday party, were enacted in a large warehouse, and well-known photographers were shooting them with the new cameras while Polaroid stockholders circulated and examined the pictures. Polaroid engineers were also circulating, with extra cameras in their pockets in case anything went wrong.

Resting on their laurels

So Fairchild won a contract to manufacture the exposure control modules along with the motor circuits and the flash control circuits. The trade press touted their victory. According to a January 1973 Electronic News report, for instance, this contract, “believed to be the largest ever issued by a camera producer to an electronics supplier,” was worth $19 million, and was “considered by some semiconductor executives as an omen of considerable future business.”

Fairchild disbanded most of its design team, pleased with their success. But the manufacturing engineers pressed on, since the cost of the product had to be reduced by three-quarters or more to meet Polaroid’s price target, and contract negotiations were to be reopened for 1974. However, said Perrino, two of the chips in the exposure control module were still in trouble.

C. Lester Hogan, who had recently left Motorola Inc. to take over the Fairchild presidency, blames Fairchild’s then-outdated manufacturing facilities. He started a modernization, but he said, “there wasn’t a lot of extra cash,” and it was not complete until sometime in 1974.

Perrino blames the IC designs as well. “The design rules used in these chips were touch-and-go with the technology,” he told Spectrum. Polaroid’s Carcia agreed: ‘‘We were pushing the fundamental technology.” Redesigning the chips was talked about, but management did not mandate it.

A matter of pride

The TI design team was also disbanded in 1972. Some left the company, some moved on to other projects. The failure, one design engineer told Spectrum, was a black mark that hurt careers.

At the highest level of TI, however, the book was not being closed. TI chairman Haggerty reportedly called his old friend Land and said, “We at TI don’t fail.” He assigned the project about $540,000 from his own budget, and told his managers to do whatever it would take to succeed. The code name Project Alpha emphasized the importance of the fresh start, and Haggerty put executive vice president Bucy in charge of it.

The failure, one design engineer [said], was a black mark that hurt careers.

As the original TI team had been disbanded, Bucy planned to assemble another one from the semiconductor division, and to ensure that this one would communicate directly with Polaroid and also have manufacturing responsibilities.

Dean Toombs, engineering director of the semiconductor group, held a series of meetings and developed a proposal for the redesign that was another break with TI’s first approach: it relied not on proven but on state-of-the-art IC technology and packaging. A circuit board only 1/64 inch thick was to hold up to four digital (not analog) ICs and eight discrete components at most. The chips would be surface mounted to the board in a miniDIP package, a method of volume assembly then new and risky but cheap. (It is now called SOT, which stands for Small Outline Transistors.)

The plan was approved by Bucy, and Henri Jarrat (then Eljarrat) selected to head the effort. At first Jarrat objected to the assignment, but gave way when told it was TI’s top priority. Given carte blanche to assemble a team from anywhere in the organization, he kept the group manageably small—only 18 people. They quickly partitioned the circuitry into three ICs and presented a six-month schedule for the redesign to Fred Bucy and Polaroid president William McCune.

Skilled specmanship

Then Jarrat had his first meeting with Polaroid engineers. He told them he could only integrate the exposure control function into three components if they waived some of their specifications. He began going down his list and to each request the Polaroid engineers said no. So Jarrat stood up, threw his papers down, and said, he recalled, “Now I know why this project is going nowhere. This will never work, and I do not want to have my name attached to a failure.” He charged out of the room. Toombs backed Jarrat’s threat. “We had to get the customer under control,” he told Spectrum.

The ability to negotiate was in part also due to the availability of working cameras to study and the construction of a prototype on which to test breadboards of the chips—luxuries denied the first TI team.

After a brief adjournment, the meeting was reconvened and from then on Polaroid negotiated specifications. For example, the 20-second time out, for taking a picture in a dimly lit room, had made the signal from the photodiode impossibly low for the first design teams and this time around was cut to 10 seconds. “The big reason for our success was Jarrat’s success at convincing them to ease the specs,” said Clark Williams, a member of the second team.

The ability to negotiate was in part also due to the availability of working cameras to study and the construction of a prototype on which to test breadboards of the chips—luxuries denied the first TI team. And when the first group did raise questions out of concern for manufacturability, recalled Buss, the only TI engineer to work on both the design and the redesign efforts, they were told, “Well, your competition can do this.” And, in fact, Fairchild engineers don’t recall that the specifications were problematical.

TI began producing the Project Alpha boards in quantity in mid-1973.

With the redesign, TI quoted Polaroid a price of about $4.10 a unit—well below the $5.75 target. Said former Fairchild president Hogan: “At the time, it cost us $10. We really believed we could get it to $6, but when TI bombed the price down to two thirds of the target price, we just had to drop out.” As for a redesign, said Hogan, “we didn’t have the money to invest that way—we had to invest in the generic fixing of the factory.”

TI created a special camera division with Polaroid as its only customer. The company made about 850 000 units in 1974 and continued to produce the design until the SX-70 and the SX-70 Model 2 were discontinued in 1977. It also spun off a few innovations, including packaging for TI’s watch displays. And the engineers on the Project Alpha team were rewarded with then substantial raises of $100 to $500 a month.

West-Bond and 3M, companies Fairchild had recruited to manufacture packaging equipment and film tape, continued to profitably produce them for other companies.

Fairchild used the BTP packaging technology it developed for the SX-70 on its high-volume plastic DIP products at several manufacturing facilities. It also took its camera control technology overseas on a tour of Japanese camera manufacturers, but after several unsuccessful months gave up and closed down the production line for the exposure control module. It continued to manufacture flash control modules for Polaroid for another year, however. Within six months to a year of losing the exposure control contract, at least half the people who had worked on the project moved to other companies, Feit recalled.

Happy ending

Could the design have gone more smoothly? Certainly better communications between Polaroid and the two semiconductor companies and among different divisions within TI and Fairchild would have eliminated some of the rough spots.

From Polaroid’s standpoint, the information it handed out was as complete as it could be. After all, several parts of the camera system were being developed concurrently, so that the system specifications could not meanwhile be finalized. Also, said one Polaroid engineer, unfamiliarity with photography impaired the IC designers’ comprehension of the data they were given.

In the eyes of the TI and Fairchild engineers, useful information was withheld, and Polaroid engineers do admit a preoccupation with secrecy.

Still, in the eyes of the TI and Fairchild engineers, useful information was withheld, and Polaroid engineers do admit a preoccupation with secrecy due to concern over competition from Kodak. Perhaps being told that certain design issues had yet to be resolved or a detailed explanation of how an SLR functions would have elicited more creative engineering from the IC designers.

Be that as it may, the SX-70 was a brilliant success. Polaroid sold some three million units of the leather-covered Model 1 with its chrome-plated trim and the plastic-bodied Model 2. (Model 3, introduced in 1975, was not an SLR.) So while the design problems both TI and Fairchild endured triggered tense moments at all three companies, their solution opened up a huge new consumer market in electronics.

To probe further

For details on the SX-70 circuitry, see “Behind the lens of the SX-70,” by Gerald Lapidus, IEEE Spectrum (December 1973, pp. 76-83).

Both Time and Life magazines featured the SX-70 camera on their covers in 1972, and discussed it in “Polaroid’s Big Gamble on Small Cameras” (Time, June 26, 1972, pp. 80-82) and “If you are able to state a problem, it can be solved” (Life, October 27, 1972, p. 48). To understand how the development of the SX-70 fit into Polaroid’s Jong history, read The Instant Image: Edwin Land and the Polaroid Experience by Mark Olshaker (Stein & Day, New York, 1978).

Frank Perrino’s version of tape automated bonding is described in U.S. Patent #3,868,724, “Multi-layer connecting structures for packaging semiconductor devices mounted on a flexible carrier,” dated Feb. 25, 1975.

From Your Site Articles

Related Articles Around the Web